Európa nagyvárosaiban, legalábbis azok történelmi negyedeiben, Budapesthez hasonlóan egyre öregedő, egyesített csatornahálózat szolgál a közterületeken összegyűlt csapadékvíz elvezetésére, amely végső soron a szennyvízhálózatba kerül. Az intenzív városiasodás, illetve az egyre hevesebb esőzések miatt megnőtt vízmennyiséget azonban a rendszer már képtelen kezelni. Nemcsak pénz nincs az átépítésére, de hely sincs, hiszen lábunk alatt egy hihetetlenül bonyolult közműhálózat húzódik.

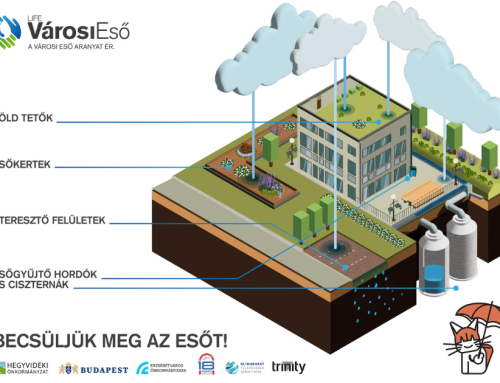

Szigeti Ferenc Albert Földgömb magazinban megjelent cikkében nemcsak a az elmúlt években kulcsfontosságúvá váló szivacsváros-koncepció emblematikus európai példáinak eredt nyomába, hanem azt is bemutatja, hogy a Városi Eső projektben résztevő budapesti önkormányzatok fejlesztéseinek köszönhetően hogyan válik hazánkban is aranyat érővé az eddig gondot okozó csapadék.

„Berlinben például komplett városrészek épülnek, amelyek szivacsként magukban tartják a vizet, védve a nem özönvizekre tervezett közműveket. Az épületen zöldtetők és zöldfalak, közöttük esőkertek és szikkasztók tartják meg a vizet, vagy késleltetik annak lefolyását, a járda pedig átengedi a víz egy jelentős részét” – osztja meg tapasztalatait Rózsa Zoltán, a Hegyvidéki Önkormányzat berkeiben működő Zöld Iroda vezetője.

Koppenhága egyik büszkesége a belvárosi Tåsinge tér, ahol az aszfalton parkoló autók egy gondosan megtervezett, szikkasztóval ellátott esőkert-láncolatnak adták át a helyüket, amely amellett, hogy összegyűjti a környező házakról lefolyó csapadékvíz jelentős részét, pihenőhelyszínként is működik. Persze, a kerékpáros-kultúrájáról ismert Koppenhágában, a szövetkezeti mozgalom hazájában könnyű, itthon pedig minden más – mondjuk erre gyakran. Ám évtizedek óta ezt a kártyát húzzuk elő kifogásként, miközben nagyon is jól tudjuk, hogy Dánia is majdnem ugyanott kezdte évtizedekkel ezelőtt, s éppenséggel Koppenhága sem rejti véka alá, hogy a Tåsinge tér esetében nagyon is nehéz volt az egyeztetési folyamat.

Vízgyűjtő terület a városban, avagy: ahol a városi eső már hazánkban is aranyat ér

A LIFE Városi Eső-program 2021-es kezdetekor még az sem volt egyértelmű, hogy egyáltalán ki tud itthon esőkertet tervezni, s nem voltak egyértelműek a felelősségi körök és a szabályozás sem.

A domborzati viszonyai miatt a dombvidéki árvizek által fokozottan veszélyeztetett fővárosi 12. kerületben a budai hegyek aljában található Győri út rendszeres elöntésének problémáját akarták megoldani a szakemberek, eredetileg egy nagyobb, felszín alá süllyesztett ciszternával. Ám az előzetes vizsgálatok eredményei szerint nem feltétlenül ott kell kezelni egy problémát, ahol az jelentkezik: például nem a város sűrűjében, ahol a közművek miatt még egy fát is nehéz ültetni, nemhogy egy hatalmas ciszternát besüllyeszteni a föld alá… Ráadásul több, kisebb megoldással sokszor hatékonyabban lehet kezelni egy problémát.

Városi környezetben mindenhol hihetetlenül bonyolult a víz lefolyásának modellezése, hiszen lényegében minden útpadkát, továbbá a csatornahálózatot is figyelembe kell venni. A 12. kerületet – a jobb tervezhetőség érdekében – vízgyűjtő területekre tagolták, amely kimutatta, hogy a Győri úton gyakran tapasztalt elöntések kezelését a hegy tetején, a Sváb-hegyen kell kezdeni. „A Jókai Mór Általános és Német Nemzetiségi Iskola tekintélyes méretű épületének, valamint a szomszédos templomnak a tetejéről érkező csapadékvizet szerettük volna megfogni terepszint alatti tározók és esőkert létrehozásával. A Pünkösdfürdő parknál kísérleti célzattal épült, kavicsos vízmegtartó réteget használó esőkert tervezői éppen annak kísérleti jellege miatt nem vállalták a kivitelezést, így egy amerikai magyar tájépítésznél lyukadtunk ki, aki a Seattle-módszerrel (ahol egy humuszos réteg fogja meg nagyon hatékonyan a vizet) tervezte az esőkertet” – ecseteli Rózsa Zoltán a megvalósítás rögös útját.

Ám szembejött a valóság: kiderült, hogy az iskola gépészetének a dugulás elkerülése érdekében nagyon is szüksége van arra, hogy a csapadékvíz néha átöblítse a csatornát, az egyházzal pedig tulajdonjogi kérdésekben nem jutott dűlőre az Önkormányzat. Végül egy három elemből álló, moduláris, bővíthető, felszín alatti tározót épít az Önkormányzat a közelbe, amelynek vizét kisebb zöldfelületek öntözésére fogja használni.

A 18. kerületben ugyan részletes lefolyásvizsgálat nem, de a problémás útszakaszok feltérképezése megtörtént, s az Önkormányzat az így megállapítható legproblémásabb helyszínt jelölte ki a beavatkozásra.

Felszín alatti szikkasztók, vízmegtartó közeggel rendelkező, fás árok és esőkert egyaránt fogja szikkasztani itt a vizet, már csak azért is, mert a külföldi gyakorlattal ellentétben a Fővárosi Csatornázási Művek nem engedélyezi az esőkertek túlfolyójának hálózatra kötését.

Címlapfotó: Kissimon István

Hagyj üzenetet