A klímaváltozás hatásai és a megváltozott hidrológiai feltételek miatt paradigmaváltásra van szükség a (csapadék)vízgazdálkodásban. Ez a témakör jelenleg több dokumentumban is szabályozásra került, ezek közül a Kvassay Jenő Terv, azaz a Nemzeti Vízstratégia talán a legfontosabb, amely a települési csapadékvíz-gazdálkodást a hazai vízgazdálkodás legelmaradottabb területeként azonosítja, és paradigmaváltást sürget.

Nemzeti Vízstratégiánk Kvassay Jenő Terv (KJT) néven a magyar vízgazdálkodás 2030-ig terjedő keretstratégiája és 2020-ig terjedő középtávú intézkedési terve.

A KJT célja a társadalom és a víz viszonyának a feltárására támaszkodva intézkedések megfogalmazása, hogy a világot fenyegető vízválságot hazánk elkerülhesse, annak már mutatkozó jelei ellen időben megtehesse a szükséges intézkedéseket.

A víz megőrzése a jövő nemzedékek számára az élet és a biztonság mással nem pótolható feltétele, és a gazdaságunk erőforrása. A vízzel való fenntartható és hatékony gazdálkodás nemzeti stratégiánk alappillére.

A KJT különösen fontosnak tartja a természetes folyóvizek védelmét és azok természetes állapotának megtartását, valamint a mezőgazdaság vonatkozásában a természeti adottságokhoz jobban igazodó tájgazdálkodás megvalósulását, így ezek tekintetében a természetvédelem és ökológia igényeihez igazodó vízgazdálkodási keretrendszert vázol fel. Mindez összhangban van a Nemzeti Környezetvédelmi Programmal, a Nemzeti Vidékstratégiával, illetve a Nemzeti Fenntartható Fejlődési Stratégiával. A KJT továbbá felhívja a figyelmet a megújuló energiák hasznosítására, konszenzusban a Nemzeti Energiastratégia által megfogalmazott célokkal.

A KJT szükségessége, kihívások

Földünk édesvíz készlete állandó, de ha egy főre vetítjük, a fogyás drámai. Az elmúlt negyven évben a 13 ezer köbméter/fő/év globális átlag 5 ezerre csökkent. A népesedési folyamatok és a klímaváltozás globális vízválsággal fenyegetnek, rendkívüli kihívás elé állítva a vízzel való gazdálkodást.Ennek elkerülésére, tompítására szorgalmazzák a világ jelentős szereplői a közös cselekvést a víz ügyeiben.

Az ENSZ-ben 2015 szeptemberében elfogadott Fenntartható Fejlődési Célok között a víz kiemelt hangsúlyt kap 2030-ig, a következő területeken:

- a vízminőség javítása a szennyezés csökkentése, a veszélyes anyagok és kemikáliák lerakásának megszüntetése, illetve kibocsátásuk minimalizálása révén, valamint a nem tisztított szennyvíz jelenlegi arányának megfelezése és az újrahasznosított víz arányának növelése,

- a vízhatékonyság növelése minden ágazatban, a vízkivétel és -szolgáltatás fenntarthatóvá tétele a vízhiány problémájának kezelése érdekében,

- integrált vízgazdálkodás megvalósítása minden szinten, megfelelő esetben beleértve a határokon átívelő együttműködést is,

- a vízi ökoszisztémák védelme, beleértve a hegyeket, az erdőket, a vizes területeket, a folyó- és állóvizeket, valamint a felszín alatti vízadókat,

- a nemzetközi együttműködés kibővítése és a fejlődő országok kapacitásfejlesztéseinek támogatása a vízzel és szanitációval kapcsolatos tevékenységekben és programokban,

- a helyi közösségek részvételének támogatása és erősítése a vízgazdálkodás és a szanitáció javítása érdekében.

Települési vízgazdálkodás a KJT-ben

A települési vízgazdálkodás érinti legközvetlenebbül a lakosságot, a háztartásokat. Az ivóvízellátás teljes körűnek tekinthető (minden településen rendelkezésre áll közüzemi ivóvízellátás, a lakosság mindössze 2%-a nem jut vezetékes ivóvízhez). A szolgáltatott ivóvíz minősége döntően kielégíti a közegészségügyi követelményeket és biztonságot, a szolgáltatók kellően felkészültek, hogy üzemzavar esetén is biztosítsák az ellátást.

A szennyvíztisztítás fejlesztése révén a közcsatornán elvezetett szennyvizek döntő többsége biológiai tisztítás után kerül a befogadókba. Ugyanakkor a kisvízfolyásokba és csatornákba vezetett tisztított szennyvizek rontják a vizek minőségét, pedig ezek készletnövelő hatása elemi kívánalom lenne. A befogadók állapota, terhelése sok esetben rosszabb, mint a szennyvíztisztítóból érkező vízminőség, függetlenül attól, hogy van-e az adott befogadó felett más engedélyes kibocsátó, így kiemelt fontosságú a befogadók illegális terhelésének feltárása.

A víztakarékosság elve, hogy a háztartásba belépő vizet minél többször felhasználjuk, ez pedig a szennyvízkeletkezés helyén a leggazdaságosabb. E kérdéskörben hangsúlyos az ún. szürkevizek környezeti ártalmak nélküli hasznosítása, elsősorban mezőgazdasági vízhasználat, öntözés céljából.

A települési csapadékvíz-gazdálkodás (benne a vízvisszatartás és vízhasznosítás) megoldása, különösen a csapadékok hevességének növekedése miatt, szakmai, intézményi és finanszírozási tekintetben egyaránt egyre súlyosabb kihívás. A víziközművek avulása (például a hálózat 250 éves kicserélési ciklusa) az elmaradt rekonstrukció fedezetének sürgős megteremtését igényli rekonstrukciós alap létrehozásával. Az elavult víziközművek működtetésének fenntarthatósági hiányosságai sürgős megoldást igényelnek. A kellő működési források, a rekonstrukciók fedezetének rendelkezésre állása, a még hátralévő fejlesztések végrehajtása elemi feltétele a kiegyensúlyozott víziközmű-ellátásnak és a felszín alatti vízkészlet takarékos, hatékony hasznosításának, a vízválság elkerülésének.

A területi vízgazdálkodás több, szakmailag sajátos szakterületet fed le (árvízmentesítés és árvíz elleni védekezés, síkvidéki vízrendezés, belvíz elleni védekezés, dombvidéki vízrendezés; mezőgazdasági vízgazdálkodás; térségi vízszétosztás, folyógazdálkodás, vízi utak, vízenergia-hasznosítás). Ezek alapinfrastruktúrája jórészt kiépült, de nem hasznosításorientáltak, defenzív jellegűek és rugalmatlanok (különösen a klímaváltozás fényében).

Vissza-visszatérően milliárdokat fordítunk árvíz- és belvízvédekezésre, ugyanakkor elszenvedjük az aszályok ugyancsak milliárdos kárait. Ezért az egységes vízgazdálkodás keretében a vízelvezetés (árvizek és belvizek elvezetése) és a vízhasznosítás összekapcsolása szükséges a vízvisszatartás eszközeivel (és ennek részeként a vizes élőhelyek rehabilitációjával és fejlesztésével, tekintettel arra, hogy a biológiai sokféleség megőrzésében rendkívüli jelentősége van a vizes élőhelyek szegényedése, az ökoszisztéma-szolgáltatások további hanyatlása megállításának), ami egyben a vízválság elkerülésének legjelentősebb eszköze is.

Fővárosi Csapadékstratégia

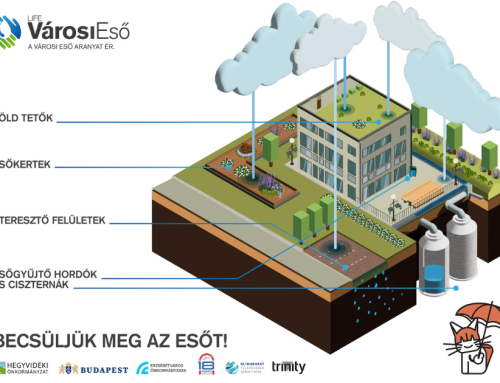

A Városi Eső program elemei a Fővárosi Csapadékstratégiához illeszkednek, amely viszont többek között a Nemzeti Vízstratégiában, a 2. Nemzeti Éghajlatváltozási Stratégiában, az MTA Nemzeti Víztudományi Kutatási Programjában, a SECAP-ban, Budapest 2021-2026-ig szóló Környezetvédelmi Programjában és a 2021-es Radó Dezső Tervben – Budapest Zöldinfrastruktúra Fejlesztési és Fenntartási Akcióterve – meghatározott irányelveket, célokat és eszközöket követi:

- Vízelvezetés fejlesztése mellett a lefolyás késleltetése, a csapadékvíz növekvő arányú helyben tartása és hasznosítása

- A városi hősziget-hatás csökkentése, a vizek (rekreációs célú) hozzáférhetőségének javítása

- Zöldfelületi, csapadékvíz-gazdálkodási és árvízvédelmi intézkedések integrált kezelése

- Felkészülés a veszélyhelyzetekre, társadalmi és egyéni felelősség tudatosítása, ehhez a jogszabályi környezet felülvizsgálata, módosítása, gazdasági ösztönző rendszer kialakítása, érintettek (pl. önkormányzatok) együttműködésének megteremtése

Kerületi akciótervek kapcsolódása, ütemezése

A Városi Eső projekt részeként Budapest 7., 8. és 12. kerületeivel a cselekvési tervek egyeztetése megtörtént, a Fővárosi Csapadékstratégia és kerületi cselekvési tervek legfőbb tartalmi elemei megegyeznek. Az egymásra épülés érdekében:

- a hidrológiai-hidraulikai modellezés eredményei elkészülnek,

- a modelleredményeket megkapják a kerületek, terv szerint 2024. év elején,

- 2024. elején külső szakértő bevonása a stratégia alkotáshoz

- 2024. közepéig elkészül a fővárosi csapadékstratégia (amely a kerületi környezetvédelmi programokban / akciótervekben már figyelembe vehető)

Hagyj üzenetet